Scientists at Plant & Food Research are using their expertise in horticulture to explore the production of fruit without a tree, vine, or bush - instead using lab-grown plant cells.

Initial trials have included working with cells from blueberries, apples, cherries, feijoas, peaches, nectarines and grapes.

Cellular horticulture, agriculture and aquaculture, the production of plant, meat and seafood products in vitro, is at the cutting edge of food technology worldwide. By growing food from cells in the laboratory there are opportunities to use fewer resources and improve the environmental impact of food production.

Food by Design programme leader, Plant & Food Research scientist Dr Ben Schon says there’s a great deal of interest and development in controlled environment and cellular food production systems, with more than 80 companies worldwide looking to commercialise lab-grown meat and seafood.

“Cellular horticulture currently has a smaller profile than cellular agriculture and aquaculture, but we believe this is a really exciting area of science where we can utilise our expertise in plant biology and food science to explore what could become a significant food production system in the future.”

Schon says the team is now 18 months into the five-year long Food by Design programme, which is funded through Plant & Food Research’s internal Growing Futures investment of the MBIE Strategic Science Investment Fund. The research has also gained support from New Zealand company Sprout Agritech, having recently being accepted into their accelerator program designed for agrifoodtech start-ups.

Schon says initial trials have used cells harvested from blueberries, apples, cherries, feijoas, peaches, nectarines and grapes. Much like lab grown meats, the challenge is to create an end product that is nutritious and has a taste, texture and appearance that consumers are familiar with.

“In order to grow a piece of food that is desirable to eat, we will need more than just a collection of cells. So we are also investigating approaches that are likely to deliver a fresh food eating experience.”

“The aim isn’t to try and completely replicate a piece of fruit that’s grown in the traditional way, but rather create a new food with equally appealing properties.”

As well as exploring the viability of cellular horticulture as a future tool for food production, Schon says the research also aims to provide better understanding of fruit cell behavior – these insights could help breed better fruit varieties that would also benefit the traditional growing methods being used by New Zealand’s horticultural sector.

This cellular horticulture research fits within Plant & Food Research’s Hua Ki Te Ao – Horticulture Goes Urban Growing Futures Direction, which is focused on developing new plants and growing systems that will bring food production closer to urban consumers.

“Globally, we are seeing rapid growth in both the vertical farming, controlled environment growing as well as cell-cultured meat spaces. It’s possible that cell-cultured plant foods could be a solution to urban population growth, with requirements for secure and safe food supply chains close to these urbanised markets,” says direction co-leader Dr Samantha Baldwin.

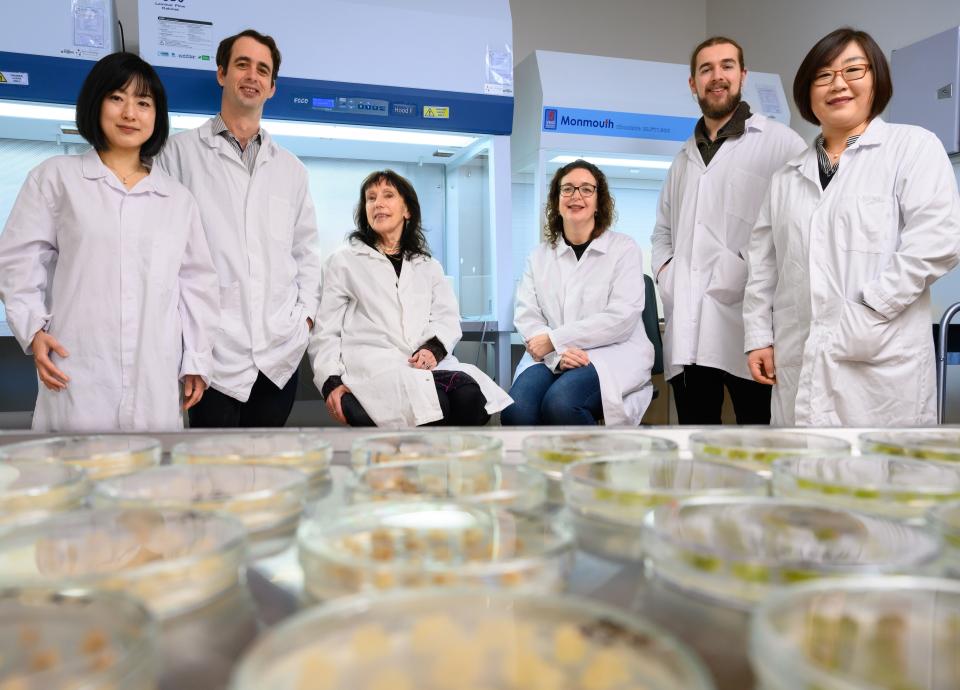

Pictured below: Clusters of blueberry cells.